Microbial Interations

Biological Interactions

With the development of microbial communities, the demand for nutrients and space also increases. As a result,

there has been a development of different strategies to enable microorganisms to persist in an

environment. Cell–cell interactions may produce cooperative effects where one or more individuals

benefit, or competition between the cells may occur with an adverse effect on one or more species in the environment. The

nature and magnitude of interaction

will depend on the types of microorganism present as well as the abundance of

the microorganisms and types of sensory systems of the individual

organisms.

Classification of microbial interactions

In addressing microbe–microbe interactions, it is

important to determine whether the interaction

is between cells of different genera or within the same species.

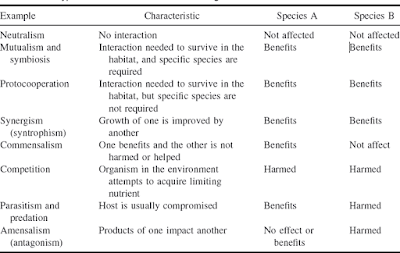

Various types of interaction of a microorganism with another microorganism and specific examples of the processes associated with

microbe–microbe interaction are presented in table 1 and 2.

Table 1: Types of Interaction between

Microorganisms and Hosts

Microorganisms can be physically associated with other organisms in a number of ways

·

Ectosymbiosis-microorganism remains outside the other organism

·

Endosymbiosis-microorganism is found within the other

organism

·

Ecto/endosymbiosis-microorganism lives both on the

inside and the outside of the other organism

·

Physical associations can be

intermittent and cyclic

or permanent

Table 2: Examples of Microbial Interactions

a – plant microbe

interaction; b - animal microbe

interaction

Neutralism

Neutralism occurs when microorganisms have no effect on

each other despite their growth in fairly

close contact. It is perhaps possible for neutralism to occur in natural

communities if the culture density is

low, the nutrient level is high, and each culture has distinct requirements for growth. It has been suggested that

neutralism may occur in early colonization of an environment without

either harmful or beneficial interactions by the microorganisms introduced.

Microbe-Microbe Interactions

1. Positive interaction: Beneficial Interactions

Some interactions provide benefits to the different partners.

(1) Mutualism (2) Protocooperation and (3) Commensalism

2. Negative interaction: Conflictual Interactions

(1) Predation (2) Parasitism and (3) Amensalism (4) Competition

Figure: Microbial Interactions: Basic characteristics of positive (+) and negative (-) interactions that can occur between different organisms

Symbiotic associations

The term symbiosis has been used to characterize various

situations where different species are found

living together. In the broadest definition, symbiosis has been used to

describe biological interactions known as mutualism, commensalisms, and parasitism.

Obligate versus facultative

Relationships can be obligate, meaning that one or both of the

symbionts entirely depend on each other for survival.

They cannot survive without each other.

Relationship may be facultative, meaning

that one or both of the symbionts

are not entirely

depend on each other and they may live independently.

1.

Positive interaction: Beneficial Interactions

Mutualism

Mutualism defines as an obligatory association that

provides some reciprocal benefit to both partners.

This is an obligatory relationship in which the mutualist and the host are

metabolically dependent on each other.

Lichen is an excellent example

of microbe-microbe mutualism

interaction. Lichen is the association between specific ascomycetes

(the fungus) and certain genera of either green algae or cyanobacteria. In a lichen, the fungal partner is termed the

mycobiont. Algal photobionts are called phycobionts and cyanobacteria photobionts are called cyanobionts.

The fungi benefit

for the carbohydrates produced by the algae or cyanobacteria via photosynthesis.

The fungus obtains nutrients from its partner by haustoria (projections of

fungal hyphae) that penetrate the

phycobiont cell wall. It also uses the O2 produced during phycobiont photophosphorylation in carrying out respiration.

The fungus provides space for algae or cyanobacteria by

creating a firm substratum within which the

phycobiont can grow. It also protects the phycobiont from excess light

intensities and other environmental stress.

Protocooperation (Synergism)

An example of this type of relationship is the

association of Cellulomonas and Azotobacter.

Azotobacter uses glucose

provided by a cellulose-degrading microorganism such as Cellulomonas, which uses the nitrogen fixed by

Azotobacter.

Another

example of this type of relationship is the association of Desulfovibrio and

Chromatium, in which the carbon and sulfur cycles are linked. The organic matter (OM) and sulfate required

by Desulfovibrio are produced by the Chromatium while reduction of CO2

to organic matter and oxidation of sulfide to sulfate required to Chromatium carried out by Desulfovibrio.

Fig. 2: Examples of Protocooperative Symbiotic Processes

Syntrophism is a protocooperative symbiotic process in

which phototrophic and chemotrophic bacteria not only exchange

metabolites but also interact at the

level of growth coordination.

Commensalism

The commensalistic relationship involves two microorganisms where one partner

(the commensal) benefits while the other species

(the host) is not harmed or helped.

There are several situations under which commensalisms may occur between

microorganisms

(1)

Commensalistic relationships between microorganisms include

situations in which the waste

product of one microorganism

is the substrate for another species.

An example is nitrification, the oxidation of ammonium

ion to nitrite by microorganisms such as Nitrosomonas, and the subsequent

oxidation of the nitrite to nitrate by Nitrobacter

and similar bacteria. Nitrobacter benefits from its

association with Nitrosomonas because

it uses nitrite to obtain energy

for growth.

(2)

Commensalistic associations also

occur when one microbial group modifies the environment to make it more

suited for another organism.

For example, in the intestine the common, nonpathogenic

strain of Escherichia coli lives in

the human colon, but also grows quite

well outside the host, and thus is a typical commensal. When oxygen is used up by the facultatively

anaerobic E. coli, obligate anaerobes

such as Bacteroides are

able to grow in the

colon.

(3)

One species releasing vitamins,

amino acids and other growth factors that are needed by a second

species.

2. Negative interaction: Conflictual Interactions

Predation

Predation is a widespread phenomenon where the predator

engulfs or attacks the prey. In the world

of eukaryotes, it is common that the larger animal eats the smaller one;

however, with microorganisms the

predator may be larger or smaller than the predator, and this normally results in the death of

the prey.

Several of the best examples are Bdellovibrio, Vampirococcus, and Daptobacter.

Each of these has a unique

mode of attack against a susceptible bacterium.

(1)

epibiotic predator with growth on the

surface of the prey. Ex. – Vampirococcus

(2)

periplasmic predator, with growth in between the inner and outer membranes

of bacteria. Ex.

Bdellovibrio

(3)

cytoplasmic predator, with growth in the cytoplasm

of the prey. Ex. Daptobacter

Figure: Cell associations: bacteria as predators on other bacteria. Bacterial parasites may

be found growing (A) in the

cytoplasm, (B) in the periplasm, or (C) on the surface of a bacterial host.

Parasitism

In parasitism, one organism (parasite) benefits from another

(host); there is a degree of coexistence between the host and parasite

that can shift to a pathogenic relationship (a type of predation).

The host may

be microbes, plants or animals.

Microbe-microbe parasitism

(1)

Mycoparasitism (Fungus-Fungus Interaction)

When one fungus is parasitized by the other fungus, this

phenomenon is called mycoparasitism. The parasitizing fungus is called hyper parasite and the parasitized fungus as hypoparasite.

Barnett and Binder (1973) divided mycoparasitism into

(i) necrotrophic parasitism, in which the relationships

result in death of the host thallus, and (ii) biotrophic parasitism, in which

the development of the parasite

is favored by a living rather than a dead host structure. The antagonistic

activity of necrotrophic mycoparasites is attributed to the production of

antibiotics, toxins, and hydrolytic enzymes.

It is used as biocontrol agent. Ex. - The fungal

genus,

Trichoderma produces enzymes

such as chitinases which

degrade the cell walls of other fungi

(2)

Mycophagy

Mycophagy or Fungivory is the process of organisms consuming fungi.

Bacterial mycophagy

- mechanisms by which bacteria

feed on fungi. Ex.- Bacteria

Aeromonas caviae feed on

fungus Rhizoctonia solani and Fusarium oxysporum.

Many amoebae are also known to feed on pathogenic fungi. The antagonistic soil amoebae are

Arachnula, Gephyramoeba, Geococcus, Saccamoeba, Vampyrella etc.

(3)

Bacterivores

Bacterivores are free-living, generally heterotrophic

organisms, exclusively microscopic, which obtain

energy and nutrients primarily or entirely from the consumption of bacteria.

Many species of amoeba are bacterivores, as well as other types of protozoans. i.e. Vorticella

(4)

Bacteriophage

A bacteriophage, also known as a phage, is a virus that

infects and replicates within Bacteria and Archaea. i.e. ds DNA phases (T4 –

phase, lambda phase), ssDNA phase (M13 phase, ΦX174).

Amensalism

Amensalism describes the negative effect that one

organism has on another organism. This is a unidirectional

process based on the release of a specific compound by one organism which has a negative

effect on another organism.

A classic

example of amensalism is the production of antibiotics that can inhibit or kill

a susceptible microorganism.

Ex. - the destructive effect of the bread mold Penicillium on certain bacteria by the secretion of penicillin.

Competition

When two or more species use the same nutrients for

growth, some of the populations will be compromised. Competition between microbial species

may be attributed to availability of nitrogen source,

carbon source, electron

donors and acceptors, vitamins, light, and water. Microbes also compete with their neighbors

for space and resources. Competition for a limiting nutrient among microorganisms leads to exclusion of slower growing

population.

For ex. - during decomposition of organic matter the increase in number and activity of microorganisms put heavy demand on limited supply of oxygen, nutrients, space, etc. The microbes with weak saprophytic survival ability are unable to compete with other soil saprophytes for these requirements.

Comments

Post a Comment